HOMILY WEEK 14 04 – Year II

God’s Ways Are Not Our Ways:

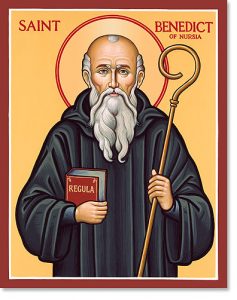

Memorial of St. Benedict

(Hos 11:1,3-5,8-9; Ps 80; Mt 10:7-15)

********************************************************

A young lad, allowed by a storeowner to lick the molasses from an empty jar, decided he should pray first, “Lord, make my tongue adequate to this occasion!”

Today’s liturgy invites us to respond to God’s love with a love that is an adequate response to God’s love for us.

The first reading from Hosea exudes with the language of love: God loved Israel from his youth, called him out of Egypt as a son, lavished tender love on Israel, taught him how to walk, embraced him, healed him, led him with kindness and bands of love, lifted him up to God’s cheek, and bent down to feed him.

Suddenly, the reading bluntly states Israel rejected God’s love and refused to return to God. In the time of Hosea, the people prospered and became either more secular or involved with pagan religions of their trading nations. They forgot the Lord who was their God, had rescued their ancestors from Egypt and had established them as a nation set apart to serve God and be an image of God on earth.

We could say the same thing has happened in our society today: wealth, technology and secularism has made possible abortion, doctor-assisted suicide, same-sex marriage, transgender self-identification, Sundays dominated by sports or recreation and not religion, a new atheism, divorce and family break-ups more than ever. Perhaps in some ways our present situation is worse than that of Hosea’s time.

God had every reason to abandon and punish Israel, but God’s ways are not ours – God offers relationship and redemption, not revenge and recrimination; salvation, not condemnation. God reacts in disappointment and anger (his heart recoiled), but does not act out of that anger. Instead, God’s compassion grows even stronger, warmer and more tender! God’s response to infidelity and idolatry is to love even more and be even more compassionate; to pour on more love and forgiveness. Pope Francis echoes this reality when he reminds us God never tires of forgiving, of showing mercy. Julian of Norwich also sees only mercy and not anger in God.

Think of the worst thing you have ever done, and picture Jesus face to face with you, forgiveness, understanding and compassion pouring out of his face, eyes and posture.

Our challenge is to let God, in Jesus, disarm us with tender love and cleanse us with his compassion. All we need do is repent as Israel does in the psalm, receive God’s tender compassionate love and forgiveness, and then go out as his disciples to do what they did then: proclaim the kingdom and love others as God has loved us – with a love that will heal them and make a difference in their lives.

Bishop Angaelos, leader of the Coptic Orthodox Church in the United Kingdom, says he is willing to forgive the Islamic State affiliates who boasted of brutally killing 21 of his fellow Egyptian Christians in Libya. He admits that offering forgiveness after such a horrific crime may sound “unbelievable” to some. Still, he says forgiveness is his responsibility as a Christian minister: “We don’t forgive the act because the act is heinous. But we do forgive the killers from the depths of our hearts. Otherwise, we would become consumed by anger and hatred. It becomes a spiral of violence that has no place in this world.” Further revealing his remarkable magnanimity, he asked that the world work to protect not just Christians, but all vulnerable people.

Today the Church honours St. Benedict, who was certainly a missionary disciple. Considered the father of Western monasticism, he was born in Nursia in central Italy circa 480 and died in 547.The little we know of his personal life comes from two documents: The Second Dialogue of Gregory the Great, and the Rule written by Benedict himself. Benedict was educated in Rome, a decadent city. After a few years, convinced God was calling him to be a monk or hermit, Benedict fled to a local village. After a brief stay with some holy men, he decided on a life of solitude. He received the monastic habit at Subiaco, and retired to a cave, where he lived alone in the tradition of the Desert Fathers. Soon, he began to attract followers and built 12 small monasteries.

Today the Church honours St. Benedict, who was certainly a missionary disciple. Considered the father of Western monasticism, he was born in Nursia in central Italy circa 480 and died in 547.The little we know of his personal life comes from two documents: The Second Dialogue of Gregory the Great, and the Rule written by Benedict himself. Benedict was educated in Rome, a decadent city. After a few years, convinced God was calling him to be a monk or hermit, Benedict fled to a local village. After a brief stay with some holy men, he decided on a life of solitude. He received the monastic habit at Subiaco, and retired to a cave, where he lived alone in the tradition of the Desert Fathers. Soon, he began to attract followers and built 12 small monasteries.

Between 520 and 530, Benedict and a few companions founded the great monastery of Monte Cassino, where he spent the rest of his life and wrote his Rule. This work became the primary influence on Western religious life for the next 600 years and is still followed by the “daughters and sons” of St. Benedict. This remarkable guide reflected the fatherly concern and charity of Benedict as he adapted the austere rule of the Desert Fathers to community life. He emphasized moderation, humility, obedience, prayer and manual labour as the way of holiness. St. Benedict is considered the Patriarch of Western Monasticism, and was proclaimed patron of Europe in 1964 by Pope Paul VI.

The Eucharist is a freely given gift of God’s gratuitous unconditional love, offering us both forgiveness and healing.

May our celebration empower us to respond to God’s unconditional love and forgiveness with the same unconditional love and forgiveness for others that will live out the gospel mandate to proclaim the good news of the in-breaking kingdom of heaven, cure the sick, raise the dead, cleanse lepers and cast out demons. May we do this generously, seeking nothing in return, and trusting in providence to provide for our needs.