HOMILY WEEK 14 02 – Year I

Wrestling with the Great Mystery:

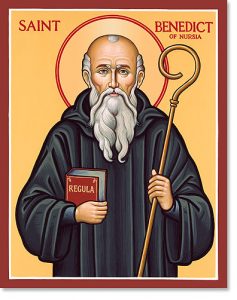

Memorial of St. Benedict

(Gen 32:22-32; Ps 17; Mt 9:32-38)

*************************************************************

Life is a mystery to be lived, not a problem to be solved.

Today’s readings invite us to wrestle with the mystery of our faith and to follow Jesus more closely.

An earnest young man visited an old monk who had the reputation for great sanctity. “Do you still wrestle with the devil, Father?” he asked him. The monk answered, “Not any longer, son. I have grown old and the devil has grown old with me. I no longer have the strength, and neither does he. Now I wrestle with God.” “With God?” the young man exclaimed in astonishment. “Do you hope to win?” “Oh no, my son,” came the reply, “I hope to lose.”

In the first reading, Jacob is alone in the wilderness. A first lesson from this reading is the importance of some solitude in our lives, to get to know ourselves better, and to deepen our relationship with God.

Alone in the wilderness, Jacob wrestles with a mysterious person, who in the end seems to be either an angel, or God’s very self. He experiences a theophany that becomes for him a blessing so significant that his name is changed from Jacob, to Israel, prefiguring the formation of a new Israel through Jesus the Messiah.

A blessing, especially of a father to a son, is crucial to the wellbeing of the blessed. This blessing is a prefiguring of the blessing that Jesus would receive at his baptism from his Father (“This is my son, the beloved, in whom I am well pleased”). That blessing empowered Jesus to go alone into the wilderness to overcome the traditional temptations that always seduced the chosen people in the wilderness (money, fame and power), and to go to the Cross to reveal the depth of the Father’s love for all humanity.

This theophany, this struggle with God leaves Jacob with a wound, which is an integral part of male initiation rites in all cultures. These rites involve some suffering and shedding of blood intended to teach young boys the lessons of male initiation, according to Richard Rohr: life is hard; you are not that important; your life is not about you; you are not in control, and you are going to die.

These rites involve some suffering and shedding of blood (circumcision is the classical initiation rite) that are intended to knock boys off the warrior path and onto the path of deeper relationships and prayer that will lead them to become more compassionate elders. Jacob’s wound and limp will serve as a reminder to him of these life lessons.

Jacob’s struggle is also symbolic of our struggle with God. Alana Levandoski, a singer-songwriter from Edmonton, whom Ron Rolheiser OMI calls a “right-brain theologian,” sings that we fear this mystery. My struggle with this mystery took the shape of running away for at least three years from a call to become a priest, until finally the hound of heaven led me to the peace of the Oblate novitiate, and eventually to a life of ministry as priest and bishop.

Classically, that spiritual journey begins with the dark night of the senses, when as youth we fight with the devil as we struggle with the energy and hormones of youth. Eventually, we are led into the dark night of the spirit, when we fight with God and hopefully are led to an ever deeper surrender of our will to that of the Father, even if that means accepting some inconvenience and suffering in our lives without resentment or bitterness, as did Jesus.

Eastern mysticism and culture posits five stages of life: We begin as a child, then become students and eventually householders with a family and career. As we enter retirement and having achieved what we are destined to accomplish in life, the invitation is to become a forest-dweller, to enter into greater solitude to reflect on our lives, its purpose and meaning, to learn more of life’s lessons. The final stage is that of a Sanyassin, a wise person and elder. At this stage, our role is to return to the community, not to “do” as much as to “be” a presence, affirming, blessing and guiding others.

The gospel presents us with Jesus, a true Sanyassin, who teaches, cares, heals and proclaims the reign of God. His very presence was a blessing to all who believed in him then, and is a blessing for all who believe in him and follow him now.

Darlene shared her fear of losing her stepson to his alcohol addiction. She suspects that he has still not let go of losing his mother, and carries a lot of anger towards his father. My hunch is that he is stuck in grief that has to move on to good grieving, and also needs to forgive his father whatever his failings were and are. He is not moving through those stages, is still fighting with the devil and afraid to wrestle with the mystery of his life.

Today the Church honours St. Benedict, who was certainly a missionary disciple. Considered the father of Western monasticism, he was born in Nursia in central Italy circa 480 and died in 547.The little we know of his personal life comes from two documents: The Second Dialogue of Gregory the Great, and the Rule written by Benedict himself. Benedict was educated in Rome, a decadent city. After a few years, convinced God was calling him to be a monk or hermit, Benedict fled to a local village. After a brief stay with some holy men, he decided on a life of solitude. He received the monastic habit at Subiaco, and retired to a cave, where he lived alone in the tradition of the Desert Fathers. Soon, he began to attract followers and built 12 small monasteries.

Today the Church honours St. Benedict, who was certainly a missionary disciple. Considered the father of Western monasticism, he was born in Nursia in central Italy circa 480 and died in 547.The little we know of his personal life comes from two documents: The Second Dialogue of Gregory the Great, and the Rule written by Benedict himself. Benedict was educated in Rome, a decadent city. After a few years, convinced God was calling him to be a monk or hermit, Benedict fled to a local village. After a brief stay with some holy men, he decided on a life of solitude. He received the monastic habit at Subiaco, and retired to a cave, where he lived alone in the tradition of the Desert Fathers. Soon, he began to attract followers and built 12 small monasteries.

Between 520 and 530, Benedict and a few companions founded the great monastery of Monte Cassino, where he spent the rest of his life and wrote his Rule. This work became the primary influence on Western religious life for the next 600 years and is still followed by the “daughters and sons” of St. Benedict. This remarkable guide reflected the fatherly concern and charity of Benedict as he adapted the austere rule of the Desert Fathers to community life. He emphasized moderation, humility, obedience, prayer and manual labour as the way of holiness. St. Benedict is considered the Patriarch of Western Monasticism, and was proclaimed patron of Europe in 1964 by Pope Paul VI.

The Eucharist is our great daily mystery of faith that nourishes us for our spiritual journey to greater maturity in our Christian faith.

May our celebration today empower us to fight the devil in ways that we may still need to, but more so, wrestle with God and with the mystery of our faith in a way that we both lose, and win.